Market Insight | Understanding the Space Supply Chain: How Raw Material Dependencies Threaten Defense Readiness?

- Oct 30, 2025

- 6 min read

by Omkar NIKAM

Introduction: The New Battlefield of Procurement

In today’s era of geopolitical fragmentation, the defense and intelligence community is grappling with an often-overlooked challenge: supply chain assurance for space systems. Satellites, propulsion units, thermal management systems, and onboard electronics, all rely on complex, globally distributed networks of suppliers. Yet, as global rivalries deepen, those very networks are becoming strategic vulnerabilities.

For decades, procurement frameworks within defense programs focused primarily on cost, schedule, and performance. But the wars of tomorrow, and indeed, the space domain of today, demand something different: resilient and traceable supply chains capable of withstanding export bans, raw-material shortages, and sanction cascades.

Defense supply chain assurance has shifted from a logistics function into a national security imperative.

1. The Strategic Pressure Points in the Space Subsystem Chain

Space subsystems, from satellite communication payloads to attitude control systems, draw components from dozens of suppliers spread across the globe. But the problem lies in where those suppliers sit in the geopolitical landscape.

Below is a strategic snapshot of the choke points most defense procurement officials are concerned about:

Every node in that chain from rare-earth magnets to semiconductor wafers, represents both a technical dependency and a geopolitical risk.

2. Geopolitical Realities Shaping Defense Procurement

The accelerating competition between the United States, China, and Russia has transformed supply chains into geopolitical chessboards.

Rare-Earth Dominance and Export Leverage

China currently refines about 90% of the world’s rare-earth elements, which are critical for satellite propulsion, electric drives, and precision-guided weapons. In 2024, Beijing introduced new export licensing measures for rare-earth permanent magnets, effectively tightening global access. Such moves are not merely economic but strategic, serving as pressure valves against rival nations.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) responded with its Mine-to-Magnet Initiative, seeking to rebuild domestic capacity for rare-earth processing and magnet manufacturing. This initiative follows earlier steps like the Defense Production Act (DPA) funding for U.S.-based separation facilities such as MP Materials in Nevada and Lynas Rare Earths in Texas.

The takeaway: material sovereignty is now national defense.

Semiconductor Vulnerabilities

Semiconductors, the “brains” behind satellite control systems, are another fragility point. The global dependence on Taiwanese fabrication giants like TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung Electronics exposes the West’s defense hardware to regional instability. The CHIPS and Science Act was the United States’ bold attempt to secure onshore production, yet the ramp-up time for full capability is measured in years, not months.

Sanctions and Counter-Sanctions

Western sanctions against Russia since 2022 have disrupted titanium and nickel supply chains vital to aerospace manufacturing. Russian conglomerate VSMPO-AVISMA was once the world’s largest titanium supplier, feeding the likes of Boeing and Airbus. Sanctions forced supply diversification, a painful but necessary process.

3. How These Pressures Translate to Space Subsystems

For defense and intelligence missions, space subsystems form the operational backbone. But their procurement pathways are unusually complex and globally entangled. Consider a hypothetical satellite subsystem chain:

Thrusters use titanium and niobium alloys sourced from Russia and Africa.

Star trackers use high-precision sensors fabricated in Japan.

Thermal panels rely on pyrolytic graphite sheets (PGS) produced primarily in East Asia.

RF amplifiers use gallium nitride semiconductors, often manufactured in Taiwan.

A single export restriction or factory outage in any one of those locations can halt production or delay a constellation launch by months.

Unlike other defense domains, space programs cannot simply “substitute” components. Each subsystem is qualified for launch environments, changing a supplier means requalification, retesting, and often recertification by agencies like NASA, the U.S. Space Force, or the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). The bureaucratic inertia multiplies risk exposure.

4. Why the Old Procurement Model No Longer Works

Historically, defense procurement operated through linear, vertically integrated supply chains. Prime contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon Technologies managed lower-tier suppliers under strict contractual oversight.

But globalization, and the subsequent fragmentation of supply ecosystems, changed that model forever.

Tier-3 suppliers today may be small firms in Eastern Europe or Asia.

Sub-tier vendors may rely on imported raw materials from sanctioned jurisdictions.

Digital twins and additive manufacturing now blur traditional boundaries of sourcing and verification.

In other words, visibility has evaporated.Procurement officers often know who supplies them, but not who supplies their suppliers.

5. The Hidden Cost of Ignorance: When Supply Chains Fail

A striking example came from the Space Development Agency (SDA) in early 2025, when it postponed a planned satellite launch because several subcontractors missed delivery milestones due to upstream component shortages.

Though the SDA did not publicly name suppliers, insiders cited shortages of advanced chips and radiation-hardened materials, components often sourced through complex foreign networks. Such failures cascade quickly: a delay in one subsystem stalls integration, which then delays launch, increasing insurance and ground-support costs.

The lesson: supply chain assurance is no longer a technical audit; it’s mission assurance.

6. New Frameworks of Assurance: From Risk Awareness to Risk Governance

Defense organizations are beginning to treat supply-chain assurance as a governance discipline, not just logistics. Several structural responses are taking shape.

a. Supply Chain Mapping and Data Fusion

Agencies are building multi-tier maps that connect suppliers to geography, ownership, and export-control exposure. For instance, the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) and U.S. Space Force have begun adopting integrated supplier intelligence databases that monitor geopolitical risk indices in real time.

Advanced analytics platforms can now overlay trade routes, manufacturing nodes, and export licensing frameworks to flag choke points before they impact production.

b. Dual Sourcing and Supplier Diversification

Dual sourcing, maintaining two or more certified vendors for critical subsystems, is re-emerging as a vital resilience measure. While it increases upfront cost, it dramatically reduces mission risk. Some programs, such as NASA’s Artemis supply framework, already mandate multiple supplier pathways for critical avionics and propulsion systems.

c. Domestic Industrial Base Investment

The U.S. Department of Defense is deploying DPA funds and Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants to stimulate domestic manufacturing of propulsion components, satellite structures, and electronic parts. Similarly, allies like Japan, Australia, and the United Kingdom are investing in rare-earth processing and component miniaturization to reduce dependency on Chinese midstream processing.

d. Cyber and Supply-Chain Integrity Audits

Hardware assurance is now integrated into cybersecurity frameworks. Agencies are moving toward cryptographically verifiable “digital pedigrees” for components, tracking each part’s journey from fabrication to final integration. This is critical to prevent tampering and counterfeit infiltration, which have been documented in past defense audits.

7. Strategic Choke Points: A Global Overview

To understand where the next disruptions might emerge, it helps to view the supply chain as a geopolitical map of dependencies.

This map underscores a sobering reality: strategic autonomy in space technology is increasingly tied to mineral and manufacturing sovereignty.

8. Integrating Resilience Into Procurement: Practical Measures

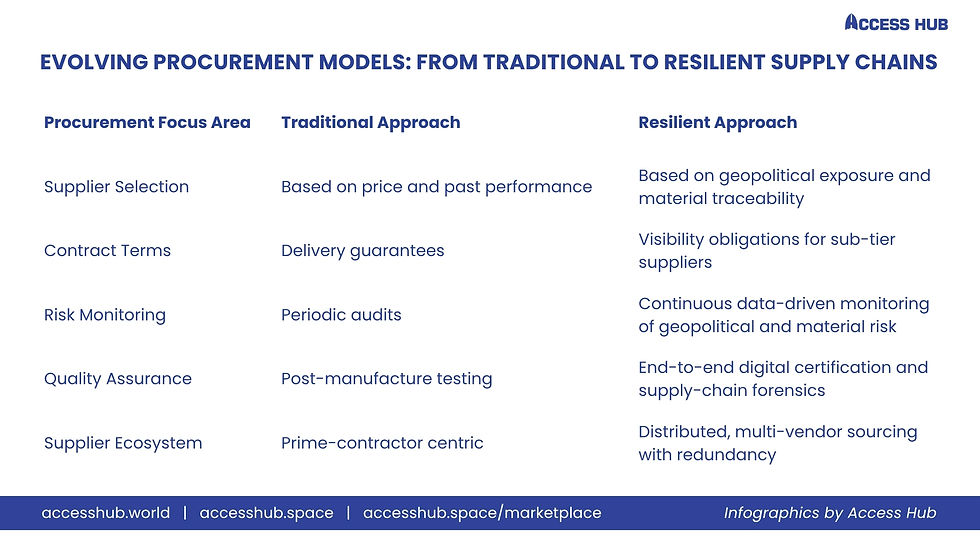

Modern defense procurement must evolve from transactional sourcing into strategic risk management. Below are emerging best practices across defense agencies and space primes.

This evolution mirrors broader defense reform efforts, emphasizing transparency, accountability, and foresight.

9. The Emerging Role of Data-Driven Supply Chain Intelligence

The next decade of defense procurement will be defined by data fusion. With thousands of suppliers connected across dozens of countries, procurement agencies are increasingly relying on predictive analytics, open-source intelligence, and AI-driven supply-risk models.

These tools analyze not only vendor reliability but also political sentiment, trade regulation patterns, and industrial indicators. For instance, a sudden rise in export-licensing delays from a given country could trigger automatic risk alerts for dependent programs.

Private-sector analytics firms and marketplace platforms are already offering such supplier intelligence dashboards to defense primes and government procurement offices, enabling data-backed decisions about sourcing alternatives before disruptions occur.

10. The Way Forward: From Awareness to Action

Supply chain assurance for space systems is no longer an afterthought; it’s the foundation of national readiness. As the defense ecosystem enters a new era of contested logistics and geopolitical realignment, procurement must pivot from reactionary management to proactive resilience planning.

The question procurement officers should ask is not “What happens if a supplier fails?” but “What happens if a nation fails?”

If a single country controls the processing of your critical subsystem materials, your system is no longer just vulnerable; it’s strategically compromised.

Conclusion

The defense sector stands at an inflection point. The forces shaping space subsystem procurement are geopolitical as much as technical. Nations that treat supply chain resilience as a core defense capability, not a budgetary inconvenience, will define the next decade of security dominance in orbit.

For those in defense acquisition, supplier management, or industrial-base strategy, this is the moment to rethink what “assurance” really means. It is not about having spare parts; it’s about having sovereign, secure, and diversified sources that align with strategic interests.

Building resilient and transparent supply chains is not optional - it is the price of strategic autonomy.

Access Hub’s mission is to connect buyers, suppliers, and decision-makers across defense, space, and intelligence sectors through verified supplier intelligence and procurement insights.

If your organization is seeking to map supplier dependencies, assess geopolitical risk, or identify alternative vendors for critical subsystems, reach out via Access Hub's B2B Marketplace.

Because in the age of contested logistics, knowing your supply chain is defending your mission.

About Author

Omkar NIKAM, Founder & CEO, Access Hub

Omkar is a consultant, analyst, and entrepreneur with over a decade of experience advising governments, space firms, defense agencies, aerospace, maritime, and media technology companies worldwide. At Access Hub, he shapes the vision, strategy, and global partnerships, positioning the platform at the crossroads of innovation and business growth.

Comments